-

Faculty of Arts and HumanitiesDean's Office, Faculty of Arts and HumanitiesJakobi 2, r 116-121 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of History and ArchaeologyJakobi 2 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Estonian and General LinguisticsJakobi 2, IV korrus 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Philosophy and SemioticsJakobi 2, III korrus, ruumid 302-337 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Cultural ResearchÜlikooli 16 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Foreign Languages and CulturesLossi 3 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0School of Theology and Religious StudiesÜlikooli 18 50090 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Viljandi Culture AcademyPosti 1 71004 Viljandi linn, Viljandimaa EST0Professors emeriti, Faculty of Arts and Humanities0Associate Professors emeriti, Faculty of Arts and Humanities0Faculty of Social SciencesDean's Office, Faculty of Social SciencesLossi 36 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of EducationJakobi 5 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Johan Skytte Institute of Political StudiesLossi 36, ruum 301 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0School of Economics and Business AdministrationNarva mnt 18 51009 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of PsychologyNäituse 2 50409 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0School of LawNäituse 20 - 324 50409 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Social StudiesLossi 36 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Narva CollegeRaekoja plats 2 20307 Narva linn, Ida-Virumaa EST0Pärnu CollegeRingi 35 80012 Pärnu linn, Pärnu linn, Pärnumaa EST0Professors emeriti, Faculty of Social Sciences0Associate Professors emeriti, Faculty of Social Sciences0Faculty of MedicineDean's Office, Faculty of MedicineRavila 19 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Biomedicine and Translational MedicineBiomeedikum, Ravila 19 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of PharmacyNooruse 1 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of DentistryL. Puusepa 1a 50406 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Clinical MedicineL. Puusepa 8 50406 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Family Medicine and Public HealthRavila 19 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Sport Sciences and PhysiotherapyUjula 4 51008 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTProfessors emeriti, Faculty of Medicine0Associate Professors emeriti, Faculty of Medicine0Faculty of Science and TechnologyDean's Office, Faculty of Science and TechnologyVanemuise 46 - 208 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Computer ScienceNarva mnt 18 51009 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of GenomicsRiia 23b/2 51010 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTEstonian Marine Institute0Institute of PhysicsInstitute of ChemistryRavila 14a 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Mathematics and StatisticsNarva mnt 18 51009 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Institute of Molecular and Cell BiologyRiia 23, 23b - 134 51010 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTTartu ObservatoryObservatooriumi 1 61602 Tõravere alevik, Nõo vald, Tartumaa EST0Institute of TechnologyNooruse 1 50411 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTInstitute of Ecology and Earth SciencesJ. Liivi tn 2 50409 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa ESTProfessors emeriti, Faculty of Science and Technology0Associate Professors emeriti, Faculty of Science and Technology0Institute of BioengineeringArea of Academic SecretaryHuman Resources OfficeUppsala 6, Lossi 36 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Area of Head of FinanceFinance Office0Area of Director of AdministrationInformation Technology Office0Administrative OfficeÜlikooli 18A (III korrus) 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Estates Office0Marketing and Communication OfficeÜlikooli 18, ruumid 102, 104, 209, 210 50090 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Area of Vice Rector for DevelopmentCentre for Entrepreneurship and InnovationNarva mnt 18 51009 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0University of Tartu Natural History Museum and Botanical GardenVanemuise 46 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0International Cooperation and Protocol Office0University of Tartu MuseumLossi 25 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Area of RectorRector's Strategy OfficeInternal Audit OfficeArea of Vice Rector for Academic AffairsOffice of Academic Affairs0University of Tartu Youth AcademyUppsala 10 51003 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Student Union OfficeÜlikooli 18b 51005 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0Centre for Learning and TeachingArea of Vice Rector for ResearchUniversity of Tartu LibraryW. Struve 1 50091 Tartu linn, Tartu linn, Tartumaa EST0

Catherine Gibson has a new book published with Oxford University Press

Catherine Gibson, a research fellow in Church History, has a new book published with Oxford University Press entitled Geographies of Nationhood: Cartography, Science, and Society in the Russian Imperial Baltic.

In the following, Gibson explains the motives for writing the book, the writing process, and who might be interested in reading it.

Motives for writing the book

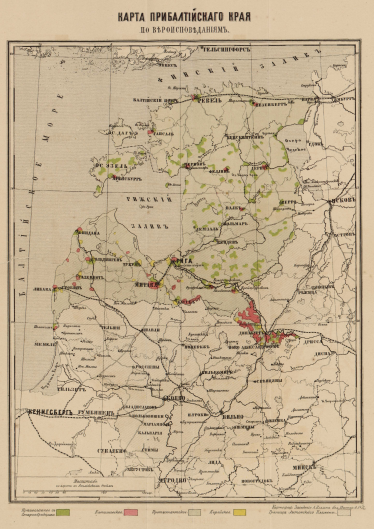

Ethnographic maps gained rapid popularity in the nineteenth century as a new form of data visualisation that was used to show where different ethnic, linguistic, and religious communities lived. As beautiful and informative as these maps appear to be, however, they were far from neutral. They quickly developed into highly politicised tools for debating ideas about identifications, loyalties, and belonging, particularly during the process of drawing new national state borders in the wake of the First World War and collapse of the Russian Empire.

Today, ethnographic maps are commonly found museums, history textbooks, or shared on social media. Yet, what can we learn about the past if we not only look at what these maps show but also ask ourselves: Who made them? Why were they made? Who paid for them? Where and how were they made? Who looked at them and read them? What did audiences think of them?

Geographies of Nationhood is her attempt to answer some of these questions by looking at the history of ethnographic cartography in the Russian Empire’s Baltic provinces. It examines the stories behind over fifty ethnographic maps, the mapmakers who made them, and their circulation, consumption, and reception in imperial society as objects of visual and material culture. Examples of maps analysed in the book include the early ethnographic maps of Estonians and Swedes in western Estland province by Carl Friedrich Russwurm, Aleksandr Rittikh’s effort to map religion in the Baltic provinces, the work of Latvian cartographer Matīss Siliņš who mapped Latvian Baptist migrant settlements in South America, and the 1920 ethnographic town plan of Valga/Valka prepared by the Estonian-Latvian Boundary Commission.

About the writing process

The book is based on research carried out as part of Gibson’s Mobilitas Pluss postdoctoral research project “Seeing Though Numbers” (MOBJD517) and the project “Orthodoxy as Solidarity”, funded by the Estonian Research Council (PRG1274). It also draws on material from her doctoral thesis, defended at the European University Institute in Italy. It is the result of more than seven years of research in archives and libraries across Russia, Estonia, Latvia, Belarus, Lithuania, Poland, Finland, Germany, and the United Kingdom.

At the outset, Gibson mainly focused her attention on archives and map collections located in the imperial capital, such as the Russian Geographical Society and Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg. As she dug deeper into the topic, however, Gibson expanded the focus to examine the array of diverse contexts and locations across the empire where innovative experiments with ethnographic mapmaking were taking place. In doing so, book brings together a breadth of historical evidence about mapmakers who have often been overlooked in traditional accounts of the history of cartography, such as bureaucrats and civil servants, publishing entrepreneurs and printworkers, clergymen and teacher, women, and local landowners and farmers. Their stories allow us to trace how cartographic visual and material culture, as well as cartographic literacy, spread among a far broader social spectrum of Baltic society than previously thought. Paying attention to ethnographic maps published in small, local printing houses or drawn by individuals with their pen and paper also allows us to consider how maps were used by non-state actors as tools of resistance, protest, and to promote alternative ways of thinking about human geography.

Who will this book be of interest to?

The book will appeal to readers interested in the history of the Baltic provinces in the Russian Empire, visual and material culture, and the history of cartography. Understanding the historical development of mapmaking is crucial for understanding how maps have come to hold such a powerful influence over popular geographical conceptions of nationhood, state-building, and border-drawing to this day.

Read more similar news